The Onion Paper

A Layered Approach to Writing (and Making Reviewers Cry)

The Onion Paper

Thesis: write your paper so it can be peeled.

Open every section with the core claim (make it impossible to miss), then ground and justify it, and only then dive into implementation details + evaluation. Keep linking back to the original claim as you go. Readers shouldn't have to excavate your contribution from a sediment layer of setup.

And because scientific reading is often skimming under time pressure, you should also design visual anchors: figures, small schematics, and short callouts that break up dense text and give the eye places to land.

The Problem: Papers That Don't Respect Fatigue

I've been reading a lot lately. By "a lot", I mean thousands of papers. Surveying the landscape, conducting literature reviews, trying to keep up with the field. And somewhere around paper 734, I had a realization:

Most papers aren't designed to be read by tired people.

They assume infinite patience, linear attention, and unlimited cognitive bandwidth. They're written as if everyone will start at word one and dutifully march through to the acknowledgments.

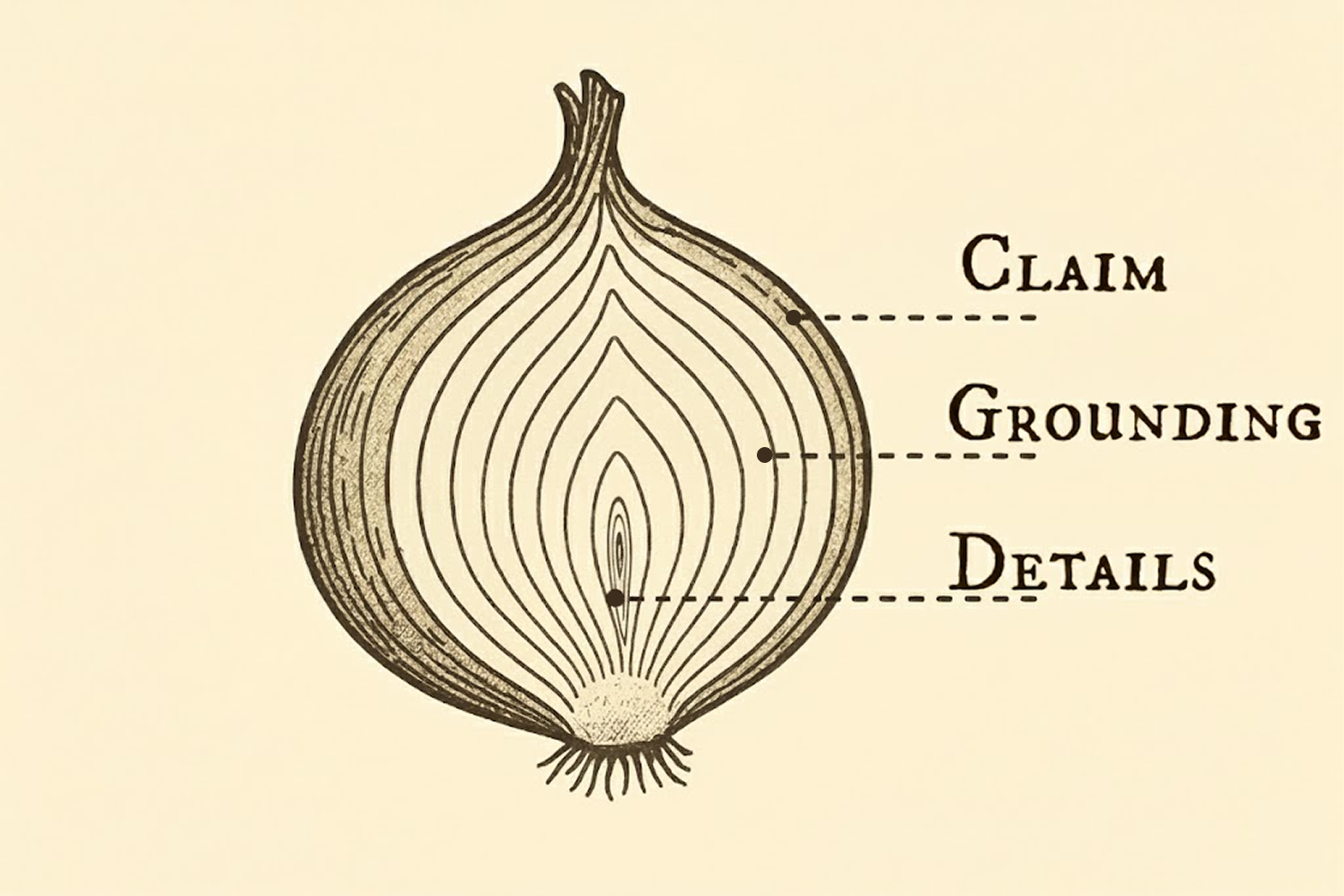

Spoiler alert: readers peel papers like onions. Most stop at the outer layer, some go deeper, and almost nobody reaches the core.

That's not how anyone actually reads. Not reviewers. Not researchers. Not even the authors themselves when they revisit their own work six months later.

We skim. We scan. We jump to figures.

We read abstracts, glance at conclusions, and only dive deep when something hooks our interest.

Most papers still fight this reality. They are not designed around it.

A Layered Approach to Writing (Yes, Like an Onion)

What if we designed papers the way we design visualizations, with layers, hierarchy, and progressive disclosure?1

Like peeling an onion, readers should be able to engage at three depths. And yes, just like onions, well-structured papers can make reviewers cry. This time, aim for tears of joy (or at least confusion reduced to manageable levels).

Layer 1: Claim (The Skim Layer)

- For readers who are tired, rushed, or reviewing 12 papers before Monday (we've all been there)

- Goal: Answer "Should I keep reading?" (or "Can I reject this in 5 minutes?")

- Content: Your core claim up front: what's the problem, what's new, and why it matters

- Comprised of: abstract, figures, section headers, first/last sentences, conclusion

Layer 2: Grounding (The Macro Layer)

- For readers who want to understand your argument's structure (the people who actually care)

- Goal: Answer "Why should I believe this?" (and "How does the argument hang together?")

- Content: Grounding + justification: positioning in related work, assumptions, trade-offs, and the logic that connects evidence to the claim

- Comprised of: introductions, transitions, related work framing, discussion of trade-offs

Layer 3: Details (The Micro Layer)

- For readers who need full technical depth (bless them, they exist)

- Goal: Answer "Can I reproduce/extend this?"

- Content: Implementation details + evaluation: algorithms, parameters, experimental setup, ablations, edge cases, failure modes

- Comprised of: detailed methods, experimental setups, mathematical formulations, appendices

Standing on the Shoulders of Storytellers

The onion paper synthesizes ideas from communication theory and narrative design that have been proven in other domains. Two frameworks in particular align beautifully with layered academic writing.

The Minto Pyramid Principle comes from Barbara Minto's work at McKinsey2. She noticed consultants buried their conclusions in pages of analysis, forcing executives to excavate the key message. Her solution: flip the structure. Start with the answer, then support it with grouped arguments, then back those arguments with detailed data.

Looks familiar? Yeah, it corresponds to the three layers: The Claim states the answer (your contribution). The Grounding groups the supporting logic (why your approach works). The Details provide the technical and evaluative evidence (enough to reproduce or extend it).

The pyramid principle emerged from business communication. Academic papers are structured arguments in a different format, and they benefit from the same hierarchy. Both need clear hierarchy, both respect limited attention, and both allow readers to stop at any depth.

Minto's key insight: readers shouldn't have to wait until the end to discover what you found. Front-load the punchline, then progressively justify and detail it.

The ABT Framework adds narrative drive. Randy Olson, a marine biologist turned filmmaker3, diagnosed a common scientific writing disease: the "and, and, and" pattern. Researchers pile facts without creating story arc. Context becomes a laundry list, methods become procedural catalogs, results become data dumps.

His fix is deceptively simple: And, But, Therefore.

- And: establish context, set up what's known.

- But: introduce conflict, tension, or a gap (your research problem).

- Therefore: present resolution, contribution, or implication.

The "But" signals why readers should care. It names what's broken, missing, or unresolved. It creates what UX designers call "information scent": readers follow the trail of conflict toward resolution. When the "But" is missing, the paper reads like one more entry in an endless catalog of studies about [insert topic here].

The three-layer structure aligns with ABT as well. Your Claim (abstract) needs one crisp ABT (readable in 30 seconds). Your Grounding sections need ABT per subsection (why this design choice? why this comparison?). Even Details benefit from micro-ABTs (why this parameter? why this encoding?).

Here's an example abstract using ABT:

"Visualization systems must balance detail with interpretability (And),

existing approaches sacrifice one for the other (But),

therefore we propose adaptive layering that adjusts based on engagement (Therefore)."

Olson warns that junior researchers fall into the "and" trap constantly, listing observations without establishing what's at stake. If you struggle to articulate your "But", your paper may lack a clear problem statement. If your "Therefore" feels weak, your contribution may not be emphasized enough.

Thinking of Papers as Systems

Here's the reframe: think of your paper as a three-tier system you design and implement. Just like building software or a visualization, you're designing a Claim (what readers see first), Grounding (how ideas connect and justify the claim), and Details (the technical specifics and evaluation). You're designing modules (self-contained sections), user flow (the path from curiosity to understanding), and progressive disclosure (revealing complexity only when sought).

This systems thinking aligns with Minto's pyramid, Olson's narrative structure, and layered information design. The Claim is your API: clean, clear, inviting. The Grounding is your logical flow: dependencies, justifications, connections. The Details are your technical and evaluative spec: reproducible, precise, complete.

The key principle: each layer should expand the previous one. The Claim previews what the Grounding explains. The Grounding justifies what the Details substantiate. No layer merely echoes another. Each layer adds a new dimension of understanding.

🧅 The Onion Paper: Ten-Layered Writing Guides

- Make the Claim Standalone. Your title, abstract, and first figure should tell a complete story, even if that's all someone reads.

- Build Narrative Momentum. Use the ABT pattern: And (context), But (problem), Therefore (solution) in every major section.

- Separate What, Why, and How. Claim = what you did. Grounding = why it works. Details = how to reproduce and evaluate.

- Use Figures as Anchors. Every figure should answer a clear question and be interpretable at a glance. Prefer active labels.

- Connect Every Section. Each layer should output what the next needs. Think of the flow as data moving through modules.

- Write for Partial Readers. Assume many will stop halfway. Add micro-summaries and make each section self-contained.

- Be Specific, Not Dramatic. Replace vague claims with concrete results. “15% error reduction” beats “significant improvement.”

- Signal Layer Transitions. Make it clear when you zoom in (details) or out (implications). Guide the reader’s focus.

- Deepen, Don’t Repeat. Each layer should add, not echo. Reference or expand, but avoid redundancy.

- Front-Load Claims, Backload Details. Lead with impact and justification, then provide technical details and evaluation. Let readers exit at any layer with value.

Peel your writing in layers: each one should stand on its own, and together they reveal the core.

Applying the Layers: A Section-by-Section Guide

Here's how traditional paper sections map to the three-layer framework:

| Section | Claim (L1) | Grounding (L2) | Details (L3) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abstract | One-sentence contribution | Key results and implications | N/A |

| Introduction | Problem + why it matters | Gap analysis and motivation | N/A |

| Related Work | What's missing | How prior work connects/differs | Specific technical comparisons |

| Method | What you did (one line) | Why this approach (justification) | Full algorithms, parameters, choices |

| Results | High-level takeaway | Analysis and interpretation | Detailed metrics, edge cases, ablations |

| Discussion | Why this matters | How it changes understanding | Specific impacts and limitations |

| Conclusion | Self-contained summary | Open questions | Future technical directions (optional) |

Reading patterns by layer: Claim readers (5 min) read abstract, look at figures, skim headers, read conclusion. Grounding readers (10-20 min) add intro, related work framing, result interpretation, discussion. Details readers (30+ min) consume everything: full methods, detailed results, technical appendices.

Practical Editing Checklist

Heres a checklist you can use to refactor your paper:

Claim Layer (L1):

- Can a colleague understand your contribution from just the title, abstract, and Figure 1?

- Does your abstract follow ABT structure (And → But → Therefore)?

- Do your section headers inform or just label? ("Results: X outperforms Y by 23%" vs "Results")

- Are your figure captions meaningful without reading the main text?

- If someone stops after 5 minutes, do they know what you did and why it matters?

Grounding Layer (L2):

- Does each section have a clear logical purpose you can articulate?

- Is there a strong "But" (conflict/gap/problem) that motivates your work?

- Can you draw the dependency graph of your argument (what builds on what)?

- Do your transitions signal movement between ideas ("Having established X, we now examine Y...")?

- Have you explained why your approach makes sense before diving into how?

Details Layer (L3):

- Can someone reproduce your work from the details provided?

- Have you separated technical choices from their justifications?

- Are edge cases and limitations clearly stated?

- Have you eliminated phrases like "it is worth noting that..." and "it can be observed that..."?

- Does each technical detail have a "therefore" (why it matters)?

Cross-layer checklist:

- Does each layer expand (not repeat) the previous one?

- Would your tired, future self be grateful for this structure?

- Can readers exit gracefully at any layer and still get value?

The Compassionate Close

Writing for the tired reader is a form of kindness.

The tired reader is still curious, still intelligent, still engaged. They just need you to meet them where they are. Some need the claim (what you did). Some need the grounding (why it works). Some need the details (how to reproduce it).

Like a well-designed system, a good paper serves all three audiences. It gives each reader a natural stopping point.

Takeaways (consider these)

We spend months perfecting our ideas and implementations, but rarely design how they're read.

We optimize for publication and neglect understanding.

We write as if everyone has infinite time and energy.

Start thinking of papers the way we think of visualizations: as layered systems designed for human perception. Systems where complexity unfolds gracefully. Where hierarchy guides attention. Where clarity respects limited bandwidth.

Because at the end of the day, we're all tired readers sometimes. And we're all better off when papers are designed with a little care and that reality in mind.

Like an onion: layers that protect, preserve, and progressively reveal what matters most.

Now all I gotta do is follow my own advice 🫣.

Practical LaTeX Visual Anchors: Tags, Badges, Callouts, and Labeled Margins

To make important elements stand out and visually group related ideas, you can use custom LaTeX structures like tags, badges, callouts, and vertical labeled margins. These help readers scan, reference, and remember key points. Below, each type is grouped with its code, a usage example, and a brief description.

1. Bold Colored Underline Tag

Purpose: Emphasize a word or phrase with a thick, colored underline.

Required packages: \usepackage{tikz}

% Bold, colored, thick underline tag (perfectly horizontal, fixed alignment)

\newcommand{\taguline}[2]{%

\tikz[baseline=(X.base)]{

\node[inner sep=0pt, outer sep=0pt, anchor=base] (X) {#2};

% draw a fixed horizontal line slightly below baseline

\draw[#1, line width=2pt]

([yshift=-1.5pt]X.base -| X.west) -- ([yshift=-1.5pt]X.base -| X.east);

}%

}

Usage:

\taguline{red}{Important}

Creates a bold, colored underline tag for emphasis.

2. Vertical Labeled Margin

Purpose: Group and label whole paragraphs or blocks in the margin (e.g., for methods, warnings, or highlights).

Required packages: \usepackage{tcolorbox}, \usepackage{tikz}

% Vertical margin with labels aligned

\newtcolorbox{labeledmargin}[2]{%

enhanced,

breakable,

frame hidden,

colback=white,

left=0mm,

right=0mm,

before skip=6pt,

after skip=6pt,

overlay={%

% vertical line

\draw[#1, line width=2pt]

([xshift=0mm]frame.north west) --

([xshift=0mm]frame.south west);

% centered label

\node[

rotate=90,

anchor=center,

font=\small\bfseries,

text=#1

] at ([xshift=-2mm]frame.west) {#2};

},

}

Usage:

\begin{labeledmargin}{red}{Warning}

This is a highlighted warning block.

\end{labeledmargin}

Visually groups and labels a block in the margin.

3. Inline Metric Box

Purpose: Show inline, visually distinct metrics or results.

Required packages: \usepackage{tcolorbox}

% Define inline metric box

\newtcbox{\metricbox}[1][]{

colback=white,

colframe=black, % change to your preferred color

boxrule=0.8mm,

arc=2mm,

left=2mm,

right=2mm,

top=1mm,

bottom=1mm,

halign=center,

valign=center,

enhanced,

nobeforeafter, % keeps it inline

#1

}

Usage:

\metricbox{42\%}

Displays a metric or result in a rounded, inline box.

4. Inline Rounded Tag

Purpose: Add a small, rounded label/tag inline with text or figures.

Required packages: \usepackage{tcolorbox}

% White rounded tag for labeling things

\newcommand{\encodingsTag}{%

\tcbox[colback=white,colframe=black]{\textsf{\footnotesize Encodings}}%

}

Usage:

\encodingsTag

Adds a small, rounded label/tag inline.

5. Colored Callout Box

Purpose: Create callouts, explanations, or visually group a figure and its key takeaway.

Required packages: \usepackage{tcolorbox}

% Callout with figure and explanation

\newtcolorbox{examplebox}[1][blue]{%

enhanced,

colback=white,

colframe=white,

borderline west={2pt}{0pt}{#1}, % <-- color parameter

left=6pt,

right=2pt,

top=2pt,

bottom=2pt,

boxrule=0pt,

sharp corners,

}

Usage:

\begin{examplebox}[red]

This is a callout box with a red bar.

\end{examplebox}

Creates a colored callout box for explanations or highlights.

These structures help you create a visually layered, skimmable, and memorable paper—making your key points stand out for every reader.

Notes & References

Below is a list of references so you can scan everything in one place.

-

Layer Cake Pattern of Scanning — Content Structure for Web Reading

Nielsen Norman Group. (2024).

https://www.nngroup.com/articles/layer-cake-pattern-scanning/

Extended: Describes how users scan content in layers, reading headings and subheadings while skipping body text. Emphasizes the importance of meaningful headings, visual hierarchy, and progressive disclosure to support non-linear reading patterns—principles that apply equally to academic papers. -

The Pyramid Principle — Logic in Writing, Thinking and Problem Solving

Minto, B. (1978, revised 1981). Minto International.

https://openlibrary.org/works/OL3012477W/The_pyramid_principle

Extended: Explains a technique for organizing ideas into a pyramid structure—starting with conclusions, then supporting arguments, then details, making them easy for readers to grasp. Teaches how to use pyramid rules to discover and develop thinking, and focus it to be compelling to your audience. -

Houston, We Have a Narrative — Why Science Needs Story

Olson, R. (2015). University of Chicago Press.

https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/H/bo21174162.html

Extended: Argues that effective science communication requires narrative structure (And, But, Therefore) to create tension and resolution, moving beyond the "and, and, and" catalog pattern that obscures significance and engagement.

[CITE THIS]

@misc{theonionpaper2026,

author = {Velitchko Filipov},

title = {The Onion Paper: A Layered Approach to Writing (and Making Reviewers Cry)},

year = {2026},

month = {january},

howpublished = {\url{https://velitchko.github.io/blog/onion-paper-2026}},

note = {Blog post, keywords: Academic Writing. Accessed on January 19, 2026}

}Use this BibTeX entry to cite this blog post in your academic work.